Globally, local governments have significant responsibilities for delivering agriculture, education, and health services, and they increasingly are forging their own strategies for tackling climate change, supporting sustainable food systems, and promoting gender equality. In fact, over the last three decades, most regions of the world have experienced progressively greater decentralization, a trend sometimes christened the “silent revolution.” Despite this broader trend, decentralization faces various challenges that hinder its intended effectiveness. For example, high turnover and low retention of skilled civil servants at the local government level undermine continuity in service provision, reduce public sector accountability to communities for project implementation, and often necessitate additional outlays in scarce resources for training new staff.

In our new journal article, we examine the factors affecting bureaucrats’ continued commitment to local government service in Zambia, which has a long tradition of pursuing greater decentralization. At the advent of multiparty democracy in 1991, the Local Government Act was introduced and stipulated the transfer of 63 functions to the country’s district councils. Successive government administrations, spanning the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), Patriotic Front (PF), and now the United Party for National Development (UPND), have prioritized enhanced decentralization in the country’s various national development strategies. In fact, the Eighth National Development Plan adopted by the National Assembly in April 2022 focuses on devolving responsibility for even more services to local authorities. Nonetheless, the country’s 116 district councils thus far have been unable to effectively fulfill all of their service delivery mandates, especially in poorly resourced rural areas. Among other factors, bureaucratic retention remains a binding constraint for improving local authorities’ capacity to deliver their assigned functions.

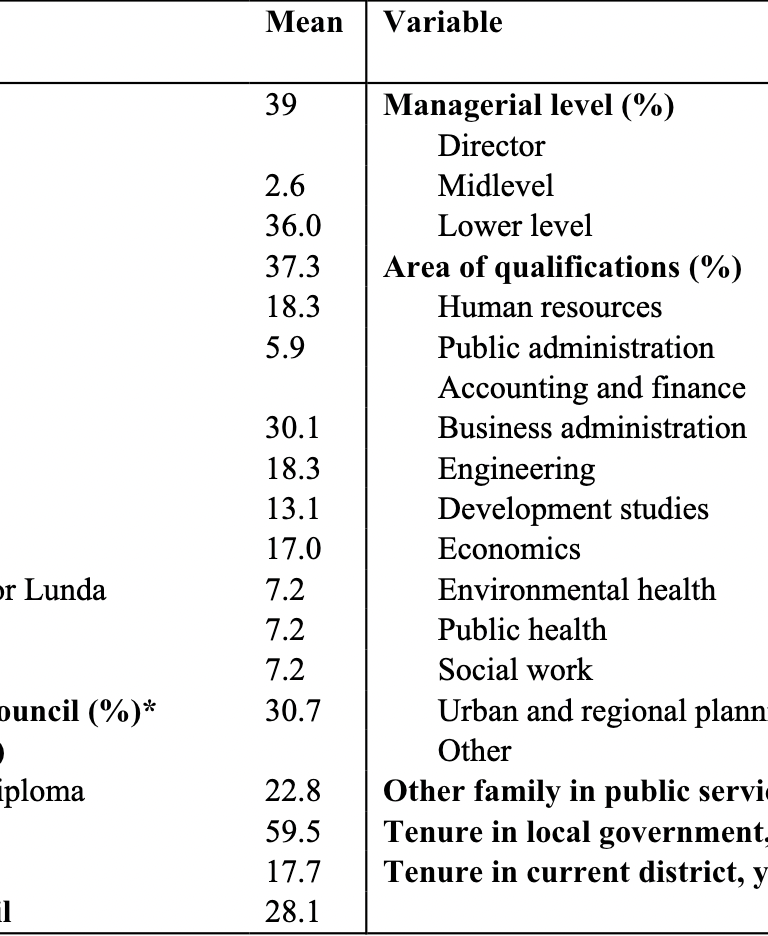

To understand factors affecting bureaucratic retention, we conducted one-on-one surveys with more than 150 bureaucrats across 16 district councils in Zambia’s Central, Copperbelt, Lusaka, and Southern Provinces. The sample included councils with both high levels of poverty as well as relative affluence, urban and rural locales, and those with mayors from the two main political parties, UPND and PF. The respondents included professionals across three levels of seniority—director, midlevel, and general workers. In addition, the respondents represented six main departments within the sampled councils: town clerk’s office, finance department, human resources and administration, public health, housing and social services, and development planning. The table below provides a snapshot of the sample.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of survey sample

Notes: N= 153 respondents. *Ethnic majority in council (%) means that the respondent’s ethno-linguistic background corresponds to the majority ethno-linguistic group in the council where s/he served at the time of the survey.

Organizational commitment was measured by asking respondents, “What career position do you aspire to have within five years?” All those who expressed interest in continuing in their current position, staying in local government but shifting to another area of expertise, or moving to a senior position in local government within their current area of expertise, were categorized as possessing more commitment to local government. Only 40 percent of the sample expressed such attitudes, while the remainder preferred to obtain jobs with the central government, the private sector, donor organizations, nongovernment organizations, or academia.

We found that one of the most substantively important factors driving civil servants’ commitment to local government was mission alignment, which refers to the congruence between an employee’s values and those of the organization that they serve. Those who noted that the most enjoyable part of their position is contributing to local government and working with community members possessed greater mission alignment. In turn, those with this attitude were more than twice as likely to express interest in staying in local government for the next five years than their colleagues who expressed alternative reasons for working in local government, such as job security, prestige, salary, managing staff, or using their expertise to design programs. On the other hand, those who are better educated are four times as likely to want to leave local government service within the next five years. This dynamic is particularly worrying since it implies that local government is likely to lose those who hold the greatest qualifications even as the councils increasingly require high-skilled workers to deliver quality services. Notably, while salary arrears, non-payment of pensions, unpredictable transfer decisions, and interference by local politicians in everyday tasks are known problems for Zambia’s councils, these factors were not significantly associated with organizational commitment.

The findings hold several policy implications. First, local government training programs need to not only focus on concrete tasks related to everyday job functions but also inculcate a sense of belonging to the local public sector. Programs that socialize new employees to the culture and mission of the organization have been successful elsewhere, such as in Egypt. Second, regular visits to the communities that bureaucrats are intended to serve could also reinforce for staff the primary purpose of their jobs. In Zambia, such visits are particularly important for better-educated civil servants who otherwise focus on office work and meetings with their superiors. Third, commitment to local public service can be enhanced through active recruitment of graduate students in the public administration, who often have a higher degree of intrinsic interest in the goals of public sector service.

Much of the research on bureaucracy emerges from high-income countries where public servants encounter vastly different resource constraints, office settings, institutional challenges, and organizational cultures than their counterparts in low-income contexts. Far too little attention is given to the aspirations, morale, and commitment of public sector bureaucrats in developing countries, and this gap is even greater at the subnational level despite the growing trend of decentralization. Our work aims to spur additional insights on this constituency who are fundamental for implementing policies and services aimed at improving the lives of poor and vulnerable communities.

For a more detailed discussion on this issue, see our recent journal article, “Organizational commitment in local government bureaucracies: The case of Zambia.”

Commentary

Bureaucratic commitment to local government service: Lessons from Zambia

July 29, 2022