It’s that time of year, when wonks fall in love – with lists of their own papers. Here at the Future of the Middle Class Initiative, we’re no exception. But as we are entering a new decade, we decided to look back further than a year or two; we decided to look back an entire decade. Previous work from our home Center, CCF, and its scholars helps to provide context for our current work on everything from the income and wealth of the middle class, to paid leave, tax credits to make work pay, access to college, housing markets, gender gaps in the effects of automation, and much, much more.

So as we set about our research agenda for 2020, here’s a look back on some work from each year of the last decade:

2010: Creating an Opportunity Society – Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill

In this book, released a decade ago, we addressed concerns about poverty and inequality in the U.S. but argued that it was time to pivot away from a single-minded focus on poverty to a much greater emphasis on opportunity and mobility out of poverty and into the middle class. We showed that the public supported an opportunity agenda far more strongly than they supported an anti-poverty agenda. We also introduced the idea of “the success sequence” — the idea that if people did just three things: graduated from high school, worked full-time, and married before having children, poverty would fall to about 2 percent and the chances of becoming middle class or better would increase to over 70 percent. In our current work, we continue to emphasize that opportunity and upward mobility into the middle class are related to access to education, to decent-paying jobs, and to stable family life.

2011: The year that income inequality captured the public’s attention – Isabel Sawhill

2011 was, like 2019, a pre-election year. At the end of 2011, a CBS/New York Times poll found that two thirds of Americans agreed the nation had too much inequality and people worried that rapid technological change was eliminating jobs. Since then, we have further explored the role of automation in our current research, found here. It has also become apparent that if 2011 was the year that income inequality captured the public’s attention; the 2010s was the decade that cemented the issue.

2012: The myth of the disappearing middle class – Ron Haskins

In this op-ed, our colleague Ron Haskins, co-director of the Center on Children and Families, challenged the idea that the middle class is disappearing. He agreed that the people at the top of the income distribution are pulling away from the rest of us. But when the insurance value of health care and the value of certain government transfer payments are included in income, the incomes of households between the 40th and 80th percentiles actually grew by nearly 40 percent between 1979 and 2007. This interpretation suggests that the middle class might not be as bad off as it appears, tying directly into an article we published just last year – Middle class incomes have slumped, stagnated, or grown, depending on the measure.

2013: Should everyone go to college? – Stephanie Owen and Isabel Sawhill

As the amount of student loans continues to rise, this 2013 report hits close to home. Every year, families of high school seniors make the tough decisions about if and where to go to college, and financial considerations are a major factor. This report ties directly in with the research we have done on where the middle class goes to college and emphasizes that while there is a significant wage premium for a college degree, it may not be the right choice for everyone.

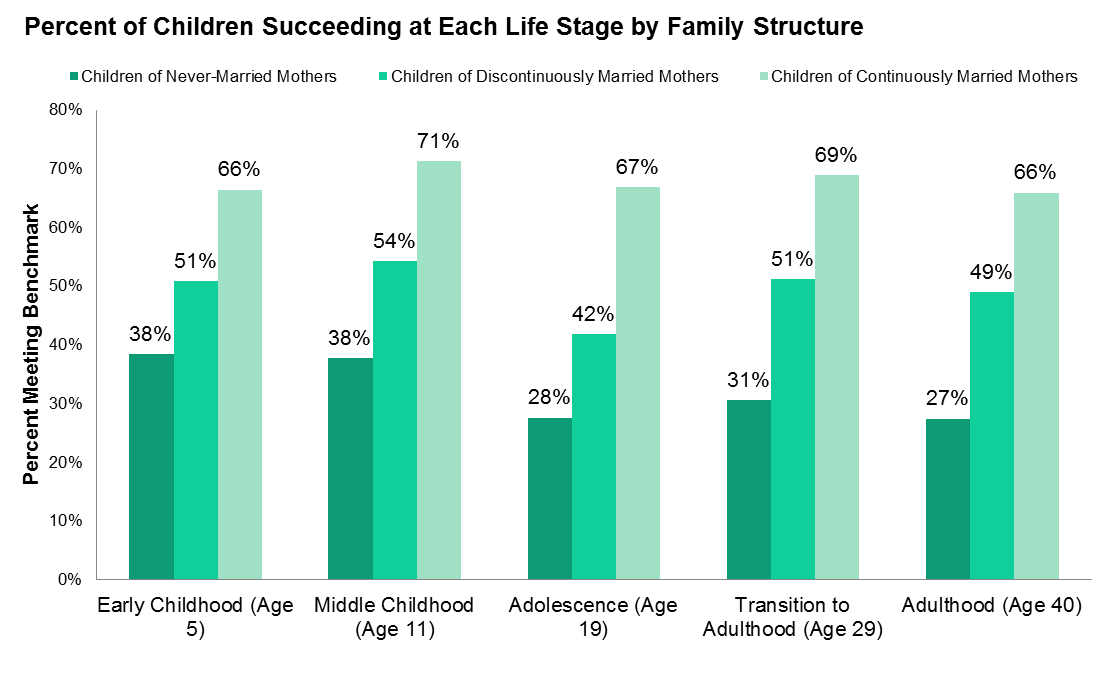

2014: The marriage effect: Money or parenting? – Kimberly Howard and Richard Reeves

Why do children raised by married parents do better? We looked here at two potential explanations: married couples have more money from two earners, and they have more opportunities for engaged parenting. We found that both factors matter a great deal, and that parenting perhaps matters a bit more than money. But promoting marriage is not the answer (even if there was a good track record of policies to do so). Instead the focus should be on helping people, regardless of their relationship status, improve their parenting skills, as well boosting the income of the poorest families.

2015: The dangerous separation of the American upper middle class – Richard Reeves

Our first ever Social Mobility Paper clearly foreshadows the creation of the Future of the Middle Class Initiative three years later. We discussed different ways that the American upper middle class separates itself from the majority, even though most wealthy people self-identify as middle class. Families in the top two percent receive about half of overall income, hold significantly more advanced degrees, and strongly feel that the U.S. is a meritocracy. We warned against sharpening class distinctions, that have certainly not abated in the meantime.

2016: 6 charts showing race gaps within the American middle class – Richard Reeves and Dayna Bowen Matthew

In 2016, we wrote a report called “Time for justice: Tackling race inequalities in health and housing,” which this article summarizes. These race gaps are more relevant than ever, as demonstrated at our recent events on Moving to Opportunity and on Zoning, taxing, and hoarding. Not only are affluent black families more likely to live in poor neighborhoods than white families, research shows that black children born into middle-quintile families are twice as likely to be downwardly mobile as middle-income white children.

2017: Race gaps in SAT scores highlight inequality and hinder upward mobility – Richard Reeves and Dimitrios Halikias

This year, the College Board created a stir by creating an “Environmental College Dashboard” to help make college admissions practices fairer – a topical issue given the Varsity Blues college admissions scandal. Taking background context into account in college admissions is however a much broader priority, not least when it comes to tackling race gaps. In 2017, we analyzed racial differences in the math section of the general SAT test. We found that average scores for Black and Latino students were clustered at the bottom of the distribution, while White student scores were normally distributed and Asian American student scores were clustered at the top. Clearly, these two minority groups will continue to be handicapped unless we find a way to improve their early environments and schooling.

2018: Defining the middle class: Cash, credentials, or culture? – Richard Reeves, Katherine Guyot, and Eleanor Krause

The condition of the middle class is a perennial political and economic issue. But who is middle class? It turns out that there are nearly as many definitions of the middle class as there are researchers studying it. An exaggeration perhaps; but not an absurd one. In this paper, we catalogue the many strategies that have been used to define the middle class, from income to occupation to aspirations. The accompanying interactive shows that income-based definitions alone can include households making anywhere from $13,000 to $230,000. In the end, we have decided to use a definition that includes the middle 60 percent of the population

2019: Six facts about wealth in the United States – Isabel Sawhill and Christopher Pulliam

This year, with the help of John Sabelhaus and Bill Gale, we have done a lot of work looking at wealth. One salient fact is that the top 20 percent holds much more wealth than the entire middle class. Going into an election year in which proposals to tax wealth are getting a lot of attention, we have tried to provide objective information on both the amount of wealth inequality and what might be done to reduce it.

While our Center and the new Initiative have evolved over the past ten years, issues relating to income inequality, upward mobility, educational opportunities, family trends, gender gaps, and racial disparities have all been consistent themes. In many of these areas, progress has been slow to non-existent. But to borrow a phrase from Max Weber in relation to politics, policymaking resembles the “slow boring of hard boards”. Much more work lies ahead. Happy New Year!

Commentary

Hindsight is 2020: Reflecting on a decade of research on the future of the middle class

December 30, 2019