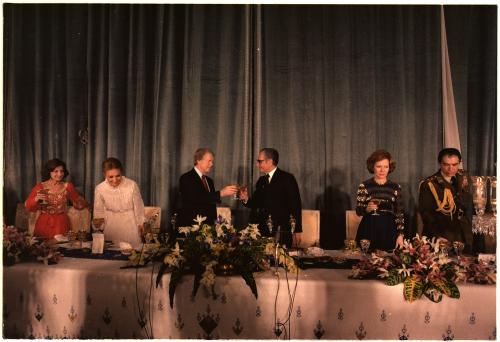

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi owed an American president and the Cold War for the zenith of his reign. The quagmire in Indochina convinced Richard Nixon that America should delegate the containment of Communist expansion to nations situated in vulnerable regions, ruled by Western-leaning leaders, equipped with formidable militaries, and known to have stable regimes.

Iran uniquely qualified in all four of those attributes for the Nixon Doctrine—or so U.S. policymakers believed. They regarded the shah as a reliable deputy marshal who would oversee law and order in the badlands of West Asia for decades to come. As for the shah on the Peacock Throne, he was looking into the distant past as well as the future. With the mightiest superpower in history at his back, he sought to restore the glory and hegemony of the Persian Empire in his own part of the world.

In 1971, two years after Nixon announced his plan, the shah put on the bash of the millennia. Sixty-eight heads of states attended a five-day gathering in Persepolis, the ancient Persian capital. The caviar and carpets were local, but all the other luxuries seemed to come from abroad. In his address to the invitees and to his neighbors, the shah insinuated that he was the modern successor of Cyrus the Great.

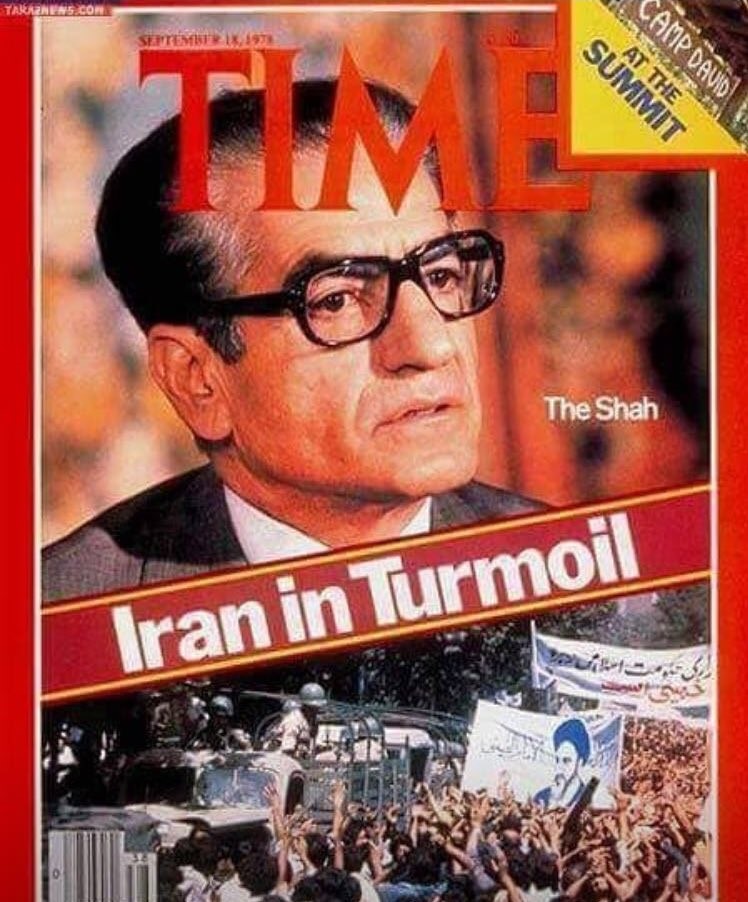

I was a roving reporter for Time magazine, and the event gave me a chance for my first visit to Iran. I came early, skipped some of festivities, and stayed afterward to meet Iranians who were discontented and, in some cases, seething: students, leftists (some no doubt Soviet agents), and Islamists who were followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

After the foreign visitors left, Khomeini distributed his own message to his fellow Iranians via tape recordings from his exile in Iraq:

Let the voice of the oppressed people of Iran be hard throughout the world…. Let them ask that this plundering and squandering be brought to an end, and that they cease behaving toward our people in this way, that huge budget of the government be spent on the wretched and hungry people… I tell you plainly that a dark, dangerous future lies ahead and that it is your duty to resist and to serve Islam and Muslim people.

Seven years later, the shah was on the brink of exile himself, and Khomeini was readying himself to return as Iran’s Supreme Leader.

The interview

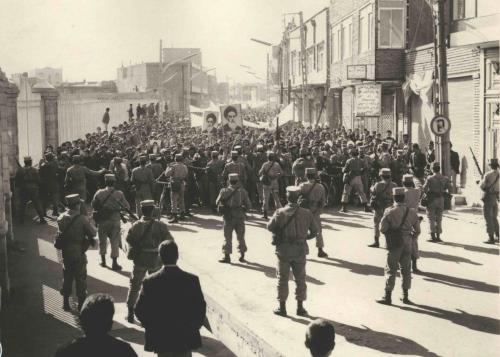

The U.S. government was slowly coming out of denial, largely because the protests and accompanying violence had intensified dramatically in early September. Washington is rarely the best vantage to assess fast-moving events thousands of miles away, especially if the U.S. government has a longstanding stake in a policy that has gone awry.

As I was preparing for a trip to see for myself, White House and State Department sources told me that the shah had the situation under control. On arrival, I joined with two colleagues, Dean Brelis from Time’s Cairo bureau and our local colleague Parvis Raein, who were more realistic. The revolution was gathering momentum by the day if not by the hour. Several Iranian government ministers we had expected to see had been fired, quit, or fled the country.

As I was preparing for a trip to see for myself, White House and State Department sources told me that the shah had the situation under control. On arrival, I joined with two colleagues, Dean Brelis from Time’s Cairo bureau and our local colleague Parvis Raein, who were more realistic. The revolution was gathering momentum by the day if not by the hour. Several Iranian government ministers we had expected to see had been fired, quit, or fled the country.

One appointment, however, was still on: an audience with the shah. Tanks and armored cars circled the Saadabad Palace in the northern outskirts of Tehran keeping back angry crowds. Their chants could be heard even from inside.

Our host was a broken man. He told us that he had declared martial law the day before because he needed six months of “discipline and calm” so that he could work with the parliament on sweeping democratic reforms. It was hardly a logical political stratagem, and he seemed not believe it himself.

Some advisors were urging him to legalize the underground Communist Party, but he was afraid that the Soviet Union would use it as a pretext for extending “fraternal assistance” to Moscow’s Iranian comrades.

We asked his view of President Carter’s robust human rights policy, especially condemnation of torture by the shah’s secret police, the SAVAK. He claimed that he had already reined in such abuses before Carter came into office. We asked if the U.S. recurring criticism of government repression was bolstering his political enemies. His answer, through pursed lips: “Well, maybe you should ask them.” Other than that, he shied from questions about U.S. policies.

When the 90-minute interview was over, he asked me to stay behind. When the others left, he called for an aide who methodically moved around the room deactivating listening devices hidden in the bookcases.

Once we were alone, he let down his reserve and self-control. He had one matter on his mind: a conviction that the CIA was plotting to overthrow him. I tried several angles to get him to elaborate: What would possibly be the American motive? Did he think that the Carter administration had given up on him? Was the United States hoping that there were moderate Iranians who would be more effective in blocking Khomeini at the head of a radical theocracy?

He refused to say anything more than that America had turned on him.

As I left the palace and made my way through swarms of protestors and police, I jumped in a cab and went to the U.S. embassy. I knew Ambassador William Sullivan and asked for an urgent private meeting. When he took me into his office, I said that I had just heard something in private from the shah to pass on, preferably in the “vault,” a windowless chamber that was believed to be secure from the most sophisticated eavesdropping. Rolling his eyes, Sullivan said, “Let me guess. He told you the CIA is out to get him. He’s whispering that to anyone who will listen. Welcome to Tehran.”

I felt more than a touch sheepish. I hadn’t gotten a scoop for my editors nor a sensitive piece of information for the U.S. government. In the article accompanying the interview with the shah, I inserted a sentence: “[T]here is even talk in high circles of another possible villain [other than the Kremlin]: the C.I.A., which is being accused of deliberately infiltrating the opposition so that its agents would be in place in the new government if the shah were overthrown.”

There was, however, one secret that very few knew: The shah’s doctors learned he had a form of leukemia in 1974. Not even the patient knew for some time. During our interview, he answered a question with a cryptic answer. Is this your gravest hour, Your Majesty? With a grim smile, he said: “We have had many hours, including some grave ones.”

An ignominious exit

Five months later, on January 16, 1979, the shah left his realm to the Ayatollahs, never to return. In addition to his lethal disease, his ignominious fate had him flying from country to country, hospital to hospital. The Carter administration grudgingly accepted him for treatment, which contributed to the storming of the American embassy in Tehran and the capture of the staff as hostages on November 4 that year. As a result, the weakening shah had to leave, initially for Panama and eventually to Egypt where he died on 27 July 1980, aged 60, in Cairo. Anwar Sadat gave him a full state funeral.

Fifteen months later, Sadat was gunned down by dissident soldiers during a parade. Joyous demonstrations broke out in Tehran, and the Ayatollahs renamed a street in honor of Lieutenant Khalid Islambouli, the ringleader of the Egyptian assassination squad. The overthrow of one key leader in the Middle East and the martyrdom of another set back American policy in the region in ways that have yet to be recovered.

Commentary

What Iran’s revolution looked like from inside the shah’s palace

January 24, 2019