The Olympics spin narratives that transcend time. They anoint sport legends in the winning athletes who dominate their sports, and in the losing competitors who face defeat but never surrender courage or grit. The sporting games tell stories of a host nation’s aspirations, which can range from recovery and renewal and elevated international status to the celebration of unique cultural traditions. The Olympics take the temperature of the geopolitical moment. Their diagnostic fills us with hope when they reaffirm our ability to transcend national divisions, or with dread when the games are highjacked by international discord.

Like its predecessors, the Tokyo 2020 Olympics is an incubator of narratives. But these Olympic Games are like no other. Coming a year behind schedule in 2021, and yet sporting a 2020 brand, it is not just that the narrative incubator has been running longer, but that the storylines are more poignant. As the first-ever Olympics hosted during a pandemic, Tokyo 2020 will provide an account of the match between science vs. virus (and supply a ledger on the vast resource inequities among nations in their access to COVID-19 vaccines). It will take measure of the rift between President Joe Biden’s United States and President Xi Jinping’s China. Hosted just six months ahead of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, Tokyo 2020 will provide ammunition to the emerging focal point of U.S.-China strategic rivalry: the competence of democracy vs. authoritarianism. But the story that Japan wants to tell the world has also shifted profoundly from when it won the 2020 bid in 2013 to the actual games. Sure, recovery continues to be the headline, but from what? While Japan has a strong case to make for its national effort to rebuild from the Triple Disaster (the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear accident), no such assuredness is yet possible in the thick of the battle the world is waging against COVID-19.

As we rapidly approach the opening ceremony on July 23, Tokyo is yet again under a state of emergency to help reduce the spread of COVID-19, and much is on the line for the Japanese government and Olympics organizers to ensure the games are conducted safely for athletes, staff, and host city residents. However, many experts still worry that not enough is being done to prevent the games from turning into a superspreader event, especially as Japan sees an uptick in cases again this month and a rise in the delta variant domestically. For one, Japan’s vaccination rollout has been slow due to limited vaccine supply, a shortage of doctors and nurses, and its own bureaucratic process; currently 22% of Japan’s population is fully vaccinated and 34% has received at least one shot. Though vaccines have meant an easing of restrictions and a return to some sense of normalcy for places like the United States, this will not be the case for Japan in time for the Olympics. It will still take some weeks yet before the majority of the population is fully vaccinated, leaving the Japanese population susceptible during the games. As a result, organizers will need to rely heavily on other science-based disease mitigation efforts, which will ensure that Tokyo 2020 looks and feels like no other Olympics in history.

Though overseas spectators were banned from attending the games weeks ago, it was announced last week that almost all domestic spectators will also be prohibited. 96% of the competitions will be closed to fans, with those allowing spectators doing so at limited capacity. Meanwhile, for athletes, there have been strict measures in place to monitor for signs of disease, such as daily testing, and mask requirements in the Olympic Village even if vaccinated. Contingencies such as a “fever clinic” with isolation rooms where PCR tests can be administered and an “isolation hotel” outside the village have been arranged. Whether these and other precautions will be enough to stop the spread during the games is yet to be seen, but recurring announcements of infections amongst staff and competitors are not encouraging.

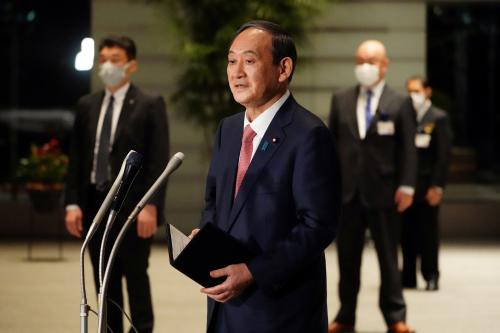

Olympics are a high season for diplomacy. Yet, there is a particular rhyme and rhythm to the Tokyo games. A main line of effort for Japanese diplomacy over the past year has been to earn a vote of confidence from world leaders on Japan’s ability to weather the COVID-19 challenge and deliver a safe Olympics. Such was the sentiment conveyed by the November 2020 G-20 leaders’ statement, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s in-person visit to the White House in April — the first by a foreign leader in the Biden administration — and the G-7 communiqué last month. But there will be no brisk diplomatic activity during these games. Attendance by foreign leaders will be sparse and the chances that the Olympics could provide a spark for a diplomatic breakthrough are low. South Korean and Japanese diplomats squabbled over the possibility of hosting a leaders’ meeting if South Korean President Moon Jae-in were to attend the games; in the end, Moon decided not to attend. Neither Biden nor Xi will travel to Tokyo, and yet the geopolitical rift of the two superpowers will frame the games — not only because of the intensified focus on the competence of democracies as an asset in strategic competition, but also because the shadow of a potential boycott of Beijing 2022 over human rights violations looms large.

Every Olympics tells a story about its host nation’s traversed path and its dreams for the future. The initial aspiration of Tokyo 2020 was to showcase Japan’s resilience and recovery from the Triple Disaster brought about by nature’s wrath and bureaucratic incompetence. Then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe saw in the Olympics a capstone to his premiership, geared to tell the world that Japan was back. But Abe resigned abruptly last summer due to illness and his right-hand man Yoshihide Suga was anointed as his successor. Today, the intended message is that the world has not been kneecapped by COVID-19. But the gamble that a safe Olympics is possible has not been lost on the Japanese public who remains deeply skeptical of the wisdom of moving forward, with two-thirds of respondents to an Asahi TV survey in late June expressing disbelief the government can deliver “safe and secure” games. And the political stakes are very different. The Olympics are no longer a crowning event but rather a litmus test for Suga’s ability to remain at the country’s helm when he faces voters later this fall. The odds are difficult given the major drop in public support for his administration (public approval stands at 31%, down three percentage points from June). The question then remains: Will Tokyo 2020 spin the narrative of renewal that Japan aspires to, given the fraught health, diplomatic, and domestic political environment?

Commentary

The many narratives of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

July 19, 2021