Admissions policies at some of the nation’s most selective schools are under intense scrutiny. But we’re not talking about colleges or Operation Varsity Blues. Selective high schools, a feature of the public education system of many U.S. cities, are under increasing pressure to become more representative of the cities they serve.

Selective high schools have much lower proportions of Black, Hispanic and low-income students than the districts they are located in. For example, of the 895 students earning a place in the freshman class at Stuyvesant, New York City’s most selective public high school, just seven are black.

Most of these schools base their admissions on academic criteria alone, typically including performance on a specialized entrance exam. A notable exception is Chicago, which operates a more inclusive, geographically-based policy. Recent attempts to reform the admission policies of these schools, most controversially in New York, have failed.

The question underlying these debates is: what constitutes fair admissions criteria? Supporters of a narrowly meritocratic approach argue it is unfair to deny, say, an Asian-American student a seat in one of these prestigious schools, in favor of, say, a Black student who scored lower on the test. Those who support a more inclusive policy argue that it is fairer to take into account socioeconomic and/or racial background in making admissions decisions.

These are not merely technocratic questions, but deeply philosophical ones. The lessons learned in these debates over selective high schools may be useful to those wrestling with similar challenges, not least the leaders of elite selective colleges.

In this paper we show the demographic composition of selective high schools in eight cities; describe the different admission policies, with a particular focus on Chicago; discuss recent failed attempts at reform of admissions policies, especially in New York City; and finally offer some thoughts on future reform at selective educational institutions.

Selective High Schools do not look like the cities they serve

Selective High Schools (SHS) are intended to serve high-achieving students and provide a strong preparation for their transition into higher education. Half the U.S. states have at least one SHS, but the majority can be found in the big cities of the North East and Midwest. There are around 165 SHS nationwide, educating about 1 percent of high school students, according to Chester E. Finn and Jessica A. Hockett, authors of Exam Schools: Inside America’s Most Selective Public High Schools.

First we examine the composition of SHS in eight U.S. cities: Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Louisville, Milwaukee, New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC, drawing on data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection site.

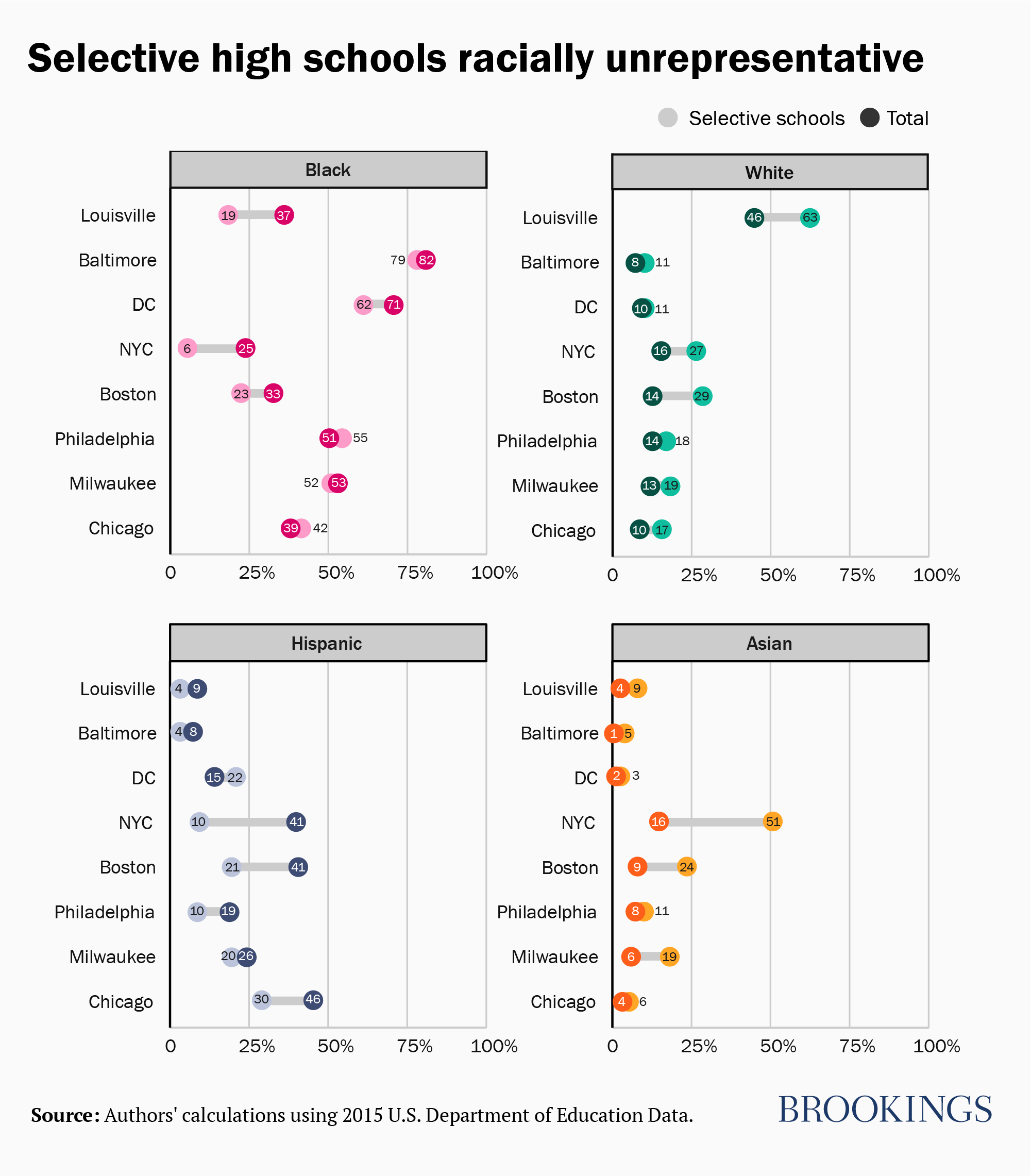

In most of these cities, the difference between the racial and economic make up of these schools and the districts they serve is striking:

While the SHS in some cities (Milwaukee, Philadelphia) are more representative of the demographics of their overall districts, disparities exist throughout each of the SHS systems. Some cities—particularly Boston and New York—have the least representative SHS student populations in terms of race, while others such as Baltimore, Louisville, and DC face greater challenges in terms of economic representation. Only in Chicago are the SHS close to being representative of the city as a whole, in terms of both race and economic disadvantage.

Why are SHS in the other seven cities unrepresentative? In large part, it is because of the significant gaps in the chances of students of different backgrounds clearing the academic bars for entry. Becoming more representative will therefore almost certainly require a recasting of admission policies. Selective high schools will have to change the way they select if they are to reflect the communities they serve.

How to get in: Admissions policies for Selective High Schools in eight cities

The admissions policies of SHS vary between cities, and sometimes between individual schools, as well as over time. The typical approach is to place a heavy weight on a tailored entrance exam, with some additional consideration given to factors such as GPA or attendance, or in some cases, essays or teacher recommendations. In the table below, we summarize the key criteria being used in each of the eight cities which are the focus of this paper. More detail on each city is then provided, with brief commentary on how admissions policies may influence the representation of different groups in the schools. We pay particular attention to Chicago, considered last.

Figure 1: Admissions processes of Selective High Schools

1. Baltimore

The city of Baltimore has four selective admission high schools that are known as “entrance criteria” schools. Each of these schools choose their students by evaluating a composite score that is calculated from a combination of grades, test scores on the Maryland School Assessment (MSA) exam, and attendance from seventh grade and the first quarter of eighth grade. Qualifying composite scores vary slightly for each school, but every entrance criteria school only accepts students who meet its minimums.

As Figure 1 shows, the SHS in Baltimore skew whiter and richer than the city as a whole. In part, this reflects variation in the academic options and performance of the city’s middle schools. Middle school students who live in higher-income neighborhoods have greater access to special academic programming, such as honors classes and gifted and advanced learning. The course grades for honors classes within these special programs are weighted at 1.10 for GPA purposes and because GPA is such a major component of the composite score (with a weight three times greater than exam scores), students who take honors classes receive a boost.

2. Boston

In Boston, there are three exam high schools, including the well-known Boston Latin School. Students seeking admission to these high schools complete an application process that involves taking the Independent School Entrance Exam (ISEE) at the beginning of sixth grade; reporting their year-end fifth grade and first semester sixth grade academic performance (GPA in math and English); and ranking schools in order of preference.

Black, Hispanic, and low-income students at every achievement level are less likely to take the ISEE than their White and Asian counterparts. Among students who do, Black and Hispanic students score around 20 percentiles lower on the ISEE than White and Asian students. Until 2007, Boston Latin admitted half of its students based on a racial quota system, but this was struck down in court following a lawsuit from a white student who narrowly missed out on a place at the school. Black and Hispanic representation has fallen sharply since.

3. Louisville

Louisville has four magnet schools that use a criteria process for admissions. Within each of these four schools, a panel of teachers reviews applications and decides which students to admit. Students’ application materials include test scores, middle school grades, essays, attendance records, teacher recommendations, and an activities and interests survey.

Louisville faces both racial and socioeconomic disparities within its selective magnet schools, as Figure 1 shows. But because the admissions processes at the magnet schools are rather opaque and data regarding applications are not publicly available, it is unclear which processes in particular contribute to the gaps in representation. It is clear, however, that admission to these schools is highly correlated with the zip code a student resides in. Students from Louisville’s seven most affluent zip codes are two to four times more likely to enroll at DuPont Manual, the most selective of the magnet schools, than the district average.

4. Milwaukee

There are five select criteria high schools within the Milwaukee Public School District. Prospective students are evaluated on a scale which combines results from an on-demand essay test, their seventh grade report card, their seventh grade attendance, their percentile rank on the Wisconsin Forward Exam, and a variety of other factors such as completion of an IB middle school program or sibling preference.

The select criteria schools of Milwaukee are more reflective of the demographic makeup of the overall district than in most other cities. This may be due to an admissions process that is more well-rounded. Despite increased representation, however, Milwaukee schools—select criteria schools included—produce some of the most significant racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps in the U.S.

5. New York City

In New York City, there are nine specialized high schools that seek to support the needs of students who excel academically or artistically. For eight of these schools, students are required to take the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT) in order to gain admission. The remaining school, which is a fine arts school, requires an audition in a talent area.

The New York specialized high schools’ reliance on a single exam score to admit students results in significant gaps in representation. This year, only seven Black students received offers to Stuyvesant High School, the most selective of the specialized schools, out of 895 seats. The admissions policies of these schools have become a heated political issue (see below).

6. Philadelphia

Philadelphia has 21 highly competitive special admissions programs that have academic standards that must be met by prospective students. This category includes seven actual schools, such as Central High School and the Philadelphia High School for the Creative and Performing Arts, as well as magnet and International Baccalaureate Diploma Programs at 14 other schools.

For applicants seeking admission to these schools or programs, their acceptance depends on their academic qualifications, with test scores playing a significant role. Though minimum applicant scores on the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA) are listed on each school’s website, many students who score below these minimums choose to apply anyway. The seven most selective schools require advanced PSSA scores in both reading and mathematics.

Although the Philadelphia selective high schools are not perfectly representative of the demographic makeup of the school district as a whole, they are much more representative than comparable systems in other cities. This may be attributed to a couple of factors. To begin, the Philadelphia system does not have strict cutoffs. Although minimum scores are presented for each school, a group of students who are below the cutoff scores are admitted each year. In addition, the principal of each special admissions high school has considerable leeway in how they enforce admissions criteria, at times overruling their school’s stated standards.

7. Washington D.C.

In Washington, DC there are six selective admission high schools. Each has slightly different admissions requirements. Only students who meet all the criteria are eligible to attend these schools. Overall, students are evaluated based on GPA, standardized test scores, recommendation letters from teachers and counselors, essays, and interviews. When there are more students eligible for entry than seats, the citywide lottery is used to allocate students to selective schools.

Because DC, like most cities, has struggled to square selectivity with diversity and representation, one of its most selective schools, School Without Walls, attempted in 2019 to modify its admissions process. Prospective students need to earn passing marks on a national standardized test in order to qualify to take the selective school admissions exam. But because Black, Hispanic, and low-income students tend to score lower on the national standardized test (just one in five Black students get a passing grade), school officials decided to implement a pilot program that would have allowed the top 15 students from each middle school to take the admissions test, regardless of whether they passed the national standardized test. But because the school did not adhere to specific regulatory requirements for changing admissions criteria, the pilot was blocked.

8. Chicago

Chicago distinguishes itself in both its selection procedures and the resulting representativeness of its schools. Like most selective schools, Chicago’s 11 Selective Enrollment High Schools (SEHS) evaluate applicants based on their overall application score. Each candidate receives a score of up to 900 that is based on the following (worth 300 points each): seventh grade GPA in math, English, science, and social studies; seventh-grade standardized test scores; and scores on the selective enrollment admissions exam. After their application score has been calculated, students can rank and apply to up to six SEHS. So far, pretty similar to other cities. But it is the specific method by which seats are allocated at these 11 selective schools that differentiates Chicago from other selective high schools in the U.S.

Since 2010, following the ending of a legal decree under which explicitly race-based affirmative action policies were pursued, Chicago has adopted a place-based procedure in order to ensure diversity in the SEHS. Using census tract data, socioeconomic status (SES) tiers were developed using indicators of disadvantage (which overlap strongly with race and ethnicity in the city). The indicators are median family income, adult educational attainment, percent of homes that are owner occupied, percent of single-parent households, percent of the population speaking a language other than English, and neighborhood school performance. The city’s census tracts are then divided into four tiers—Tier 1 representing the lowest quartile, Tier 4 the highest—so that each tier contains roughly one-quarter of the city’s school-aged children:

In allocating their seats, each SEHS designates 30 percent to top-scoring applicants, regardless of their SES tier. The remaining seats are divided equally among the four SES tiers by allocating 17.5 percent of seats to the highest scorers within each tier. This means a student in the poorest tier can get into an SEHS with a lower score than one from the richest. Effectively, the competition is between students within each socioeconomic tier, rather than between them.

One in five (19 percent) of SEHS students are from Tier 1, 22 percent from Tier 2, 23 percent are from Tier 3, and 37 percent from Tier 4. In terms of race, the result is a student body at selective schools that, while not perfectly representative, and perhaps not as racially diverse as a race-specific policy could deliver, is certainly more so than other selective admission high schools around the country. Overall, the public school district of Chicago is comprised of students who are 39 percent Black, 4 percent Asian, 46 percent Hispanic, and 10 percent White. A large portion of the district, 79 percent, is also economically disadvantaged. Within the SEHS, 42 percent of students are Black, 6 percent are Asian, 30 percent are Hispanic, 17 percent are White, and 68 percent are economically disadvantaged.

As Richard Kahlenberg, a Century Foundation scholar who helped to design the system, puts it, “the plan has proved to be the basis for a stable and enduring compromise” one that guards excellence while promoting diversity.

Underpinning the Chicago approach is a recognition that any measure of “merit” taken at a specific point in time will reflect not only ability and effort, but the background and life experience of the individual up to that point. The tier-based approach comes close to the model of equal opportunity outlined by the philosopher John Roemer. The equality of opportunity goal, according to Roemer, is to “find that policy which nullifies, to the greatest extent possible, the effect of circumstances on outcomes, but allows outcomes to be sensitive to effort.”

Of course, any system is open to abuse, and some Chicago parents have been found guilty of falsifying addresses to get their children a better chance of getting a seat at one of the schools; some do not even live in the city at all. Alternatively, those with the money can rent or buy an apartment in one of the poorer census tracts. Gentrifying areas will typically be reclassified into a higher tier, which may reduce the chances of poorer students in those areas winning a place. (This may help to explain the somewhat lower Hispanic representation, since Hispanics are less concentrated in specific neighborhoods).

How selective high school reform stalled in NYC

The admission procedures of SHS have drawn attention in a number of cities, most recently and most obviously in New York City, where Mayor Bill de Blasio has led an effort to reform the admissions practices since he first ran for office in 2013. Mr. de Blasio proposed a plan that would have eliminated the Specialized High School Admissions Test and replaced it with a system offering a place at an SHS to the top seven percent of students of each middle school.

Any change to admissions policy for all nine schools, however, requires support from state legislators. From the time it was first proposed, the mayor’s plan has been met by much opposition from parents, alumni groups, and other noteworthy individuals. A coalition by the name Education Equity was established with the sole purpose of lobbying against the proposal. Among its donors are Ronald Lauder, chairman of Clinique Laboratories, and former Time Warner CEO Richard Parsons. Many Asian American parents have also been staunchly opposed. Asian students constitute 60 percent of students at specialized high schools in 2019; up from 50 percent in 2015 (shown in our chart above).

Despite opposition efforts, de Blasio, along with the New York City Schools Chancellor of the New York City Department of Education, Richard A. Carranza, continued to push the proposal. With a new Democratic majority in Albany, prospects for its adoption seemed to improve. However, when the bill was introduced in a legislative session, it only passed the Assembly’s education committee and did not make it to a floor vote before summer recess in 2019. The proposal has stalled. Mr. de Blasio has direct control over five of the schools, and so could scrap the exam-based system for these institutions but has previously said he does not want to create a two-tier system.

There are more modest efforts underway to improve representation in New York’s SHS, however. The Discovery program offers a summer enrichment program for eligible students who take the SHSAT and score just below the cutoff. To be eligible for Discovery, students must be from a low-income household, have scored within a certain range below the cutoff score, and attend a high-poverty high school. Students who participate and complete the program requirements are then admitted to one of the specialized high schools. By the summer of 2020, 20 percent of seats at each specialized high school will be reserved for Discovery program participants. However, the impact on racial diversity is likely to be muted. More than half of the school places offered to Discovery participants in 2019 went to Asian American students.

Reforming selectivity: Potential solutions

Improving access to elite selective education institutions, including SHS, could be an important ingredient to create greater social mobility. The question is how. Reforms fall into two broad categories: investing in programs aimed at improving the admission chances of students from under-served groups without changing the entrance requirements; and restructuring the requirements themselves to give greater weight to socioeconomic background.

The following proposals fall under the first category:

- Require all students to take the entrance exams for selective high schools. Currently, there are many gaps in the racial and socioeconomic makeup of the students who choose to take the admissions exams in the first place. These gaps may be due to a lack of sufficient information within households, or other barriers, such as limited transportation to the testing location. Instituting a school day in which the entrance exam is administered to all middle school students may increase the number of students with qualifying scores from diverse backgrounds.

- Replace the unique tests schools use for admission with scores on state or national tests. Many selective high school entrance exams, including the ISEE in Boston and the SHSAT in New York, test students on curriculum that has not yet been taught in school. As a result, the students who perform best on the exam often are those who had access to prep courses or tutoring. In Boston, many Black, Hispanic, and low-income students perform well on the fifth-grade standardized test, but just a year later do not score well on the ISEE exam. This suggests that using a standardized test that is more aligned with the curriculum already taught in schools may decrease a portion of the racial and socioeconomic gaps present in current entrance exam scores.

- Provide parents and students with better and more accessible information about schools and the admissions processes. Increasing school resources to provide on-demand preparation and coaching by school administrators could help increase diversity by incorporating students into the process who otherwise may not have applied to selective programs at all. Relying on parents and students to navigate a complex application process often shuts out disadvantaged students.

- Increase access to advanced academic offerings. In cities like Baltimore, many students who attend middle schools in low-income areas do not have access to advanced or honors courses and are therefore disadvantaged in comparison to other students who can get a GPA boost from these higher-weighted courses. Expanding access to these programs throughout all middle schools could help level the GPA distribution so that not only students who attend middle schools in affluent areas can achieve highly-weighted GPAs. (Obviously this has advantages well beyond SHS admissions).

- Provide extra learning opportunities for less advantaged students. Boston, for example, has instituted the Exam School Initiative, a summer and fall ISEE-prep program for children from underserved areas and has expanded enrollment from 450 to 750.

In each of these examples, the goal is to get more children from less advantaged backgrounds above the admissions bar, rather than changing the bar itself. As such, they are likely to have relatively modest effects given the stark disparities by race, income level, and geography in these cities. The more radical approach is to change the admissions criteria itself, in order to explicitly take background into account. Mayor de Blasio’s proposal would have significantly altered the student bodies of the SHS in New York. But as demonstrated by the political events surrounding his reform efforts, a plan such as this may require going through difficult administrative processes and withstanding staunch opposition from parents, alumni, and others who favor the existing system.

The New York Mayor and other reformers might do better instead to look to Chicago’s use of area-based geographical tiers. One advantage of this system is that it retains the high-stakes entrance examination but takes inequality into account by having students with similar backgrounds compete against each other rather than pooling students from all backgrounds into one group.

The most radical option is for cities to simply abolish their selective high schools. The evidence for their impact on long-run outcomes is mixed. A number of studies have compared long-run outcomes for students who scored just below and just above the passing score (i.e. with a regression discontinuity design). Reviewing evidence from studies of the New York and Boston schools, Dynarski concludes that there is a “precisely zero effect of the exam schools on college attendance, college selectivity, and college graduation.” A 2018 study of the Chicago schools by Barrow, Sartain and de la Torre comes to similar conclusions concerning college enrollment rates. It is possible that students who scored much higher do reap benefits (or that those who scored considerably lower could do so if admitted). The overall picture however is that students from those schools do well, but many of them were going to do well anyway. Perhaps the energy, political capital, and money going to these schools could be better spent elsewhere.

Lessons for the Ivy League?

The issues facing selective high schools are similar to those affecting many elite colleges, including Harvard. The FBI sting, Operation Varsity Blues, uncovered a cheating scheme used by rich parents to get their children into selective colleges. But the deeper problem is that most of these colleges take more students from families in the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from those in the bottom 60 percent. The weighting of various characteristics of applicants – SAT, GPA, personal essay, legacy status, athletic ability, race, economic background, geography, for example – obviously has a huge influence on admissions decisions.

For colleges too, there are some options for improving access while retaining some academic screening mechanisms. There have been proposals to apply geographical quotas to improve representation. Danielle Allen, for example, suggests that colleges could admit the best performers within each nine-digit zip code.

Now there is a new tool for colleges to use, the College Board’s Environmental Context Dashboard (ECD), quickly dubbed an “adversity score”. The ECD combines a wide range of social and economic factors relating to a student’s neighborhood and high school. Colleges are using the ECD to inform admissions decisions, on the basis that a student who overcomes more significant hurdles to achieve a certain academic standard is likely to be more worthy of a place than one who achieves it from a more comfortable background. In the fall of 2019, at least 150 colleges will begin using this new measure. The use of the ECD has been attacked, predictably, as “lowering standards” or undermining meritocracy. Used well, it should be seen as a way to maintain standards and provide a more truly meritocratic system.

Perhaps some colleges will look to Chicago’s selective high school system and, armed with the ECD, take bolder steps towards a more representative student body. How about taking 20 percent of a freshman class from those with the best academic credentials, and then 20 percent from each quartile of the ECD distribution, again based on academic performance but within a comparable peer group?

The approach taken to selection in U.S. selective educational institutions is likely to come under increasing pressure, especially if there are further moves away from race-based affirmative action. The need for these schools and colleges to better represent the nation is pressing. Taking social and economic background into proper account when allocating places provides a useful path forward to more diverse and representative classes. Institutions like Stuyvesant High School and Stanford University can be elite without being elitist. But only with a serious reform of their admission policies, and therefore their admission philosophies.